Art and Engineering: How Dan Wright’s Fast Fine Art Is A Long Slow Metal Chase

Artist Daniel Wright discusses his racing-inspired sculptures, the inspiration behind them, and the process by which he sculpts and casts them.

Special to THE AUTO CHANNEL

By Louise Ann Noeth

Photos courtesy the author

We who choose to admire art, and perhaps purchase ones that “speak” to us in some way, rarely have a clue about the tedious journey the piece took to get to our eyeballs and then inveigle its way into our hearts. Cast investment art such as bronze sculpture is a long haul from concept to creation.

For sculptor, racer, engineer Daniel Wright it could be said that every finished bronze or stainless steel cast sculpture he turns out is a doctoral thesis of creative expression, a fervent process that brings into being that which danced and tumbled in his head until it escaped with conviction through his fingers.

Art is personal, and Wright’s expressions all flow through automobiles and speed machines. In 1995, after a stint at Mattel modeling little girl toys, he moved to Utah, and got a job at the state University teaching grownups how make medical things. But, it was from his volunteer work, as tech inspector of land speed record machines for the Utah Salt Flat Racing Association (USFRA) that set afire the artist in the engineer.

“It’s one of the best jobs in the world because I take a guided tour through each and every Bonneville entry, fascinated to find the racer’s ingenuity and creativity,” he explained. “The Bonneville Salt Flats is one of the last places that permits and encourages mechanical innovation by unfunded amateurs to compete at the very highest levels in a machine built at home.”

Wright views most forms of American racing as simply “motorsports entertainment” rather than real racing. Citing drag racing, he explained: “In the 1960s one could show up at an AHRA or NHRA Top Fuel meet with a self-built dragster and compete for top honors. That can’t happen today. Those cars and bikes today are very narrowly defined in order to ‘keep the field competitive.’ That is to say, to make the race TV friendly.”

His latest creation, his 26th, is an investment grade 1:8 scale ‘29 Model A on ’32 rails roadster based on the highly influential Sadd, Teague & Bentley racecar.

Cast hollow, in stainless steel and bronze, it was designed to be usable as cremation urn complete with an O-ring sealed access panel in the underside. Finding a tad of whimsy in grief, Wright engraved “Long-Term Parking” on the removable access panel.

“These materials can survive for thousands of years in harsh conditions and not deteriorate,” he said, noting an all-bronze version is in the wings.

“Someday, thousands of years from now, some archaeologists will find one of these cars, or motorcycles. They will look at with wonder and determine that the person inside must have been a person of very high status to be provided with such a vehicle in the afterlife. They would not be entirely wrong.”

Wright got his first good, long look at the Sadd, Teague & Bentley racer when he helped club member Hugh Coltharp bring the car to be displayed at the 2015 USFRA’s Annual Awards Banquet.

“Simple. Honest. It looked fast and immensely powerful standing still. I began the process that night taking a bunch of photos,” he recalled.

Teague had nothing to do with the crafting of the model save being the most respected man in the sport for decades; his humility and accomplishments are stunning. Asked for his impressions based on photos of the model Elwin “Al” Teague offered without hesitation:

“Dan’s model of our 250MPH Blown Fuel Roadster is an absolutely awesome, beautiful work of art. I am impressed not only by the extremely high degree of authenticity, but how well it represents a lakes, or Bonneville type roadster.

“We raced ours from 1960 through 1998, competing on both dirt and salt. I was the main driver, but George Bentley set a record at El Mirage in the late 1990’s. Our best one-way pass clocked at 268MPH.”

This art form is not easy. Many skills are required and the process has a substantial learning curve, so you better have plenty of patience in reserve. There are 10 basic steps that each casting must pass through to go from idea to affixing a “for sale” tag. Wright takes five of those steps every time he wanders into shepherding another sculpture into existence leaving the foundry to tango through the other five.

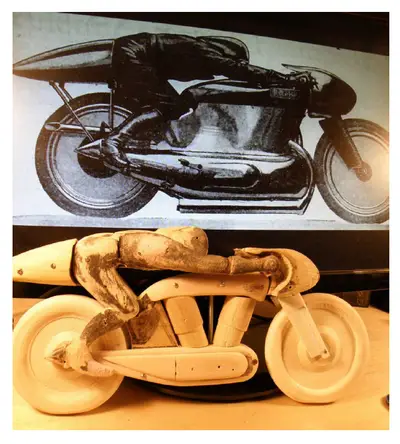

Sadd, Teague, and Bentley car in wood and plastic resin using a monster head for sizing the roll cage. |

It starts with creating an original model; Wright often uses wood and bondo with the occasional dash of 3D printing, or CNC machining.

Once he is satisfied with the original model it is time to drop the thing into a generous bath of silicone to make a 2-part mold. Because the roadsters are much larger, Wright realized he needed more control of the hollow casting process and a built himself a custom “Rotational Molding Machine.” The man will not be deterred.

Final wax casting of the roadster ready for foundry work. Here we see wheels, engine parts, body, cockpit, exhaust pipes, parachute pack, bellypan, and front axle. |

Next comes the wax copy job. Molten wax is poured into the 2-part silicone mold and swished around until an even coating covers the entire inner surface. This step is repeated until the desired thickness is achieved.

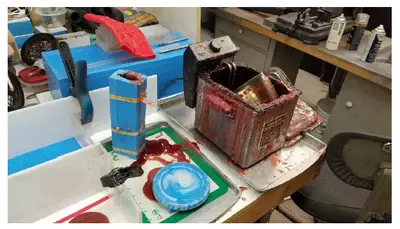

“Casting top quality waxes is difficult and only after much experimentation with various wax formulas did I settle on hard red casting wax,” he confessed.

The wax copy is then “chased”, an arty term that simply means Wright tidies up the copy with a arsenal of little styling tools to clone it as much as possible to his original.

Enter foundry folk. While Wright is still very much in control of the expression, the foundry will now sprue, slurry, burnout, pour, and release before handing Wright his bronze or stainless creation that he must once more “chase,” or cleanup with finish work. Understand this last step is a whopper of a time eating tedious process that might best be thought of as receiving an ugly duckling into which you release a gorgeous swan of a thing.

Raw castings from the foundry that require final finishing work. Surprisingly, most of the finishing is in the underside of this model.

Let’s go back a few steps for a bit more clarity. Spruing is a process where wax sprues are attached to provide a route to pour in the molten metal of choice. That done, its slurrydippin’ time. The sprued wax copy is dipped into liquid, ceramic slurry the consistency of a milkshake, or latex paint, then into a gritty, sand-like stucco.

Think of a chocolate-dipped ice cream bar rolled in a fine layer of crushed nuts and you get the idea. Both combine to form the ceramic shell. Once nice and dry the process is repeated – how many times depends on the size of piece, the bigger the art, the thicker the shell will need to be. Off to the kiln it goes for a burnout and a pour where the dried ceramic coated wax copy is placed upside-down to ‘liberate” the wax by draining the melted material. If your cerebral cortex just lit up with the term “Lost Wax Process” you’re spot on.

Wax gone, the ceramic shell remains in the kiln to harden as well as be brought up to a sweltering hot temperature, the ceramic shell has to be hot because otherwise the temperature difference would shatter it when the molten metal is poured inside, or “cast.”

The filled shells are then allowed to cool before the release begins. The ceramic shell is hammered and sandblasted away, releasing the rough casting.

Silicone molding process. Inside is the roadster being formed from the mold masters. It requires an overnight curing process of no less than 12 hours. |

Wax casting process. Two-piece mold into which he has poured the wax for the front axle of the roadster. |

Remember those sprues? They, as well as runners and gates, other foundry-added pouring bits are also faithfully recreated in metal and this excess must be cut off with a band saw. The photos of the Joseph Wright and the Jakob Henne bike pieces show how things come from the Foundry.

The last step is called metal-chasing, or cleanup where the sculptor works the casting until all the telltale signs of the casting process are eliminated. Such tools as saws, grinders and files remove the excess metal and smooth flaws.

The welder and the grinder skills are as vital to the outcome of this sort of work as is the original modeler. Welding is often part of the final step where the various pieces cast are filled and joined before final polishing — yet another laborious specialty skill.

“Not many folks see grinding as a precision operation,” laughed Wright. “But grinding in these highly visual areas is indeed precision work. If one gets careless, and gouges into the work, that damage has to be repaired by TIG welding using appropriate metal matching Filler Rod. That welded area must again be ground, offering perfect opportunity to recreate the previous mistake and damage.”

Lather rinse repeat.

Wright uses a couple different foundries to cast his work. One is mainly an art foundry, but they don’t tell him about any mistakes he shows up with at the door.

“They are way too nice for that,” revealed Wright. “They politely take my parts and fix them themselves.”

Less work for him, but the art foundry does not provide a path to learn the “error of his ways” and improve his future processes.

Wright also works with a special precision production foundry that mainly operates using high-volume automated processes.

“They don’t generally do much art,” revealed Wright who feels privileged to get his stuff in the door. “However, they tolerate me because I approach my work from an engineering standpoint. With their help, and brutal honesty, I have learned how to make best use of the investment casting process.

“When I take in pieces that aren’t right for their process, they tell me ‘No’ and then explain the problems as they arise in the casting process and suggest fixes that I might apply. That open, direct honesty, and willingness to take the time to educate me allows me to steadily improve. Honest to God, I consider some portion of every foundry invoice to be ‘Tuition.’”

Wright entered the scale model scene crafting resin-cast land-speed machines in 1999, then moved into creating polished metal sculptural fine art that is used as trophy art for those who achieve at the very highest levels of land speed racing during the USFRA’s World of Speed on the Bonneville Salt Flats.

As for his art sculptures doubling as cremations urns, it was his father’s wish be not buried, or entombed and upon his passing Wright searched in vain for cremation objects of beauty and permanence that was available for a “car guy” crossing the finish line.

“Most who have lived during the 20th century had a life that involved automobiles,” observed Wright. “For some like me, the automobile was a central theme of their life’s work, or a lifelong passion. I have been motivated to spend much of my time creating automotive artwork.”

It is due to this deep, personal connection that Wright no longer sculpts active racecars, having learned a hard lesson about choosing subjects to model.

“I have beautiful, 1/43 scale resin models of both Tom Bryant’s Competition Coupe and Sam Wheelers Motorcycle. Both those vehicles took the lives of people who were friends of mine. I choose not to profit from that work. One must never forget that racing is dangerous business and the desired outcome is not assured,” said Wright somberly.

When pressed, offering that people might instead viewing their purchase as a way to honor the fallen to keep their memory vibrant, he rejected that thinking saying: “I cherish their memory and would not want to be thought of as some how benefiting from the loss of a fellow racer. Money has a way of changing everything,” he offered.

Several members of the Bryant family witnessed the 200 MPH gut wrenching, violent tumble at the 2009 Speed Week that cost Barry Bryant, 46, his life. They respect Wright’s sentiment, yet treasure the little grey and black model.

“People loved that car, and it surely is a keepsake for our family,” said Dan Bryant who noted that the model is sitting exactly where his father placed it in his office before he passed on a few years back. “I have no problem with anyone making and selling a model of it.”

Carol Wheeler, wife of the late, gentle genius motorcycle racer Sam, echoes Bryant’s thinking.

“Sam absolutely loved that model, and today I treasure it,” said the widow after 45 years of marriage. “When they die, you don’t love them any less. I would be thrilled if Dan modeled the bike Sam died in, but I don’t know if anyone would buy it but me. I have no problem with artisans making a profit, more power to him.”

Of Wright’s limited series of nine 1:43 scale resin models, fewer than 50 were made of any given speed machine. In some cases, Wright’s model is the only version available.

For the Thomson & Tradup #7795 Danny Boy Streamliner team it was the first time for such an honor.

“We were happier than punch that some one wanted to model our car,” said owner/driver Ed Tradup whose partner Richard Thomson set a 342 MPH class record. “Richard took all my records, but I still have driver bragging rights to the car’s terminal velocity at 348 MPH.”

Back in 2000, together with his wife Kristeen, the couple fabricated a Class G Fuel Streamliner powered by a pair of 1000cc Bullet Bike Motors.

“My design had more in common with the current crop of motorcycle streamliners than it did with most streamlined cars, but it did have four wheels, and it was fast,” Wright explained reminding that the desired outcome is not assured.

“My sweet wife of 45 years drove in 2012. At 240 MPH she hit a course marker, got startled, and she twitched. That’s all it took to lose control of the machine. I was fortunate to get her back, with a bit of added titanium holding her together, but the car was destroyed. Now that I have some distance and perspective from the wreck, I see it all as an exciting and wonderful thing that we got to do. We got away with it!”

Joseph Wright rides the Zenith motorcycle 1930 in Cork Ireland to 150 MPH on a raised bed highway. Working from an illustration that ran in an Irish newspaper, Wright used this as his modeling guide. (By the way, the bike is not an Excelsior and the newspaper artist placed the exhaust pipes in the wrong location.

The same year Wright began crafting the USFRA’s “Fastest Motorcycle of the Meet” World of Speed Trophy using Irishman Joseph Wright’s (no relation) Zenith motorcycle from 1930 as his muse. It was so well received that he also turned out a few sets of investment castings of the bike and then tackled Burt Munro’s legendary Indian streamlined bike.

Wright was then asked to create the trophy for Fastest Vehicle of the Meet and for the past three years produced the 40 USFRA Class Record Award plaques.

“The racers have been very complimentary of my work, and the fact that the guys living on the cutting edge of speed appreciate what I do is something I find very satisfying,” he confessed.

How long has he been at this arty stuff? That depends on how you figure it. It all started in 1967 with a laminated oak and walnut cutting board he made for his mother. In 1972, he married Kristeen and she has been chopping away on it ever since.

Hired in at Mattel in 1984, he taught himself car sculpture and sketching once he realized people would pay him to build stuff.

“I was off to the races,” mused Wright who was recently described by a pal as a “pathological fabricator” and imagines he’ll be building ‘stuff’ as long he is able.

At Mattel he worked in the Girls Toys Department rendering into life the visions of others, magical pieces to stimulate the imagination of little girls worldwide. Here he honed the skills required to go from idea that today allow him to present sellable investment art.

“Nowadays, I’m spoiled,” he chuffed. “I like to create pieces for me. It has been most rewarding, and I am very fortunate to have such creative freedom. When others enjoy my work is the sweet frosting on top of a very good cake.”

Would he accept a commission to sculpt their racing machine? Maybe. Because the nature of this artwork is complex, slow and labor intensive, Wright’s annual output is quite limited. He tries to produce two new pieces a year together with a couple of smaller ones if the muse shows up.

“My full time job teaching prototype fabrication for its BioMedical Engineering Program at the University of Utah pretty well takes up a lot of my available time,” he explained. “So If I were to take on a commissioned project, I have to let something else go slack.”

On track to retire next spring, things might change but until then you’d have to convince him that you have a better idea, and be willing to turn over at least four Clevelands to underwrite the process. For now, Chris Karamesines Chizler dragster and Bob Leppan’s Gyronaut Bike designed by Alex Tremulis are next to be crafted in Wright’s studio workshop.

Wright generally sculpts in wood for its ease of working and its ability to hold detail. As most sculptors, he is self-taught, and struggled with symmetry issues until taught himself CAD design.

“These pieces are my impression of the incredible streamlined creations one sees at Bonneville,” confessed this modern day “Geppetto” who does not create the air-cheating shapes out of his imagination and discovered that smooth, flowing shapes lend themselves best to hand sculpting, while crisp, mechanical details reward time spent modeling with the computer.

“I find interesting is that it takes about the same amount of time to sculpt a piece by hand from photos as it does to 3-D model it in CAD software, and CNC machine, or 3-D print the part. So each of my sculptures generally ends up being an amalgam of pieces developed the ‘old way’ – by hand – and other bits created in the most modern digital manner.”

In pursuit of simple speed, all is sacrificed to reduce aerodynamic drag, an exquisite example of “form follows function” that Wright strives to further reduce to their essence.

If you would like to see Wright’s work in person, you’ll find him at most of the speed meets held each summer on the Bonneville Salt Flats, or look for one of his sculptures offered up at Mecums Annual Motorcycle Auction. Wright’s work was described as “so retro its futuristic,” by the “Faces of Utah Sculpture” Director who oversees the annual exhibition.